News & Insights

Failing forward: experiments and lessons from building legal AI prototypes

Why we’re prototyping with Legal AI

The truth is rather awkward but worth saying out loud: despite offering something rare in the legal world – quality, peer-reviewed open access content – we’ve recently seen a significant drop in website traffic to these resources.

The problem isn’t that people no longer need this content, but that the way people discover and use our content has changed and continues to evolve. We believe that few people have the patience to rummage through websites and instead expect to find it inside an AI-powered tool they’re already using, whether that’s ChatGPT or specialist legal AI platforms like Harvey.

This realisation is both worrying and liberating. It is worrying because our carefully crafted website might quickly become a museum piece. On the other hand, it is liberating because it forces us to think bigger: perhaps our content shouldn’t live and die by page views alone, but should travel, be replicated, remixed, and embedded in the new tools lawyers around the world are starting to use.

This is why we’re exploring new ways for our content to be used and distributed, using AI. It’s not about launching finished products or features, because we’re not a software company. It’s about creating provocative glimpses of what you can do with our content, so others can pick them up and develop climate-aligned features in their own legal platforms and processes.

Why influence matters more than ownership

Before we climb aboard the Legal AI bandwagon, sirens blaring, we have to admit one simple fact: we’re not a tech company, we’re a non-profit.

Yes, we’ve built some unusual in-house strengths with research, design and data science to create and test working prototypes at speed. But the skills needed to polish those concepts into secure market-ready platforms don’t sit well with us – that’s the task of the well-funded start-ups or law firm incubators who are already swarming the legal tech marketplace. Competing with them would be like showing up at the Formula 1 race in a go-kart we built in the shed. But here’s the fun part: our go-kart can go places where the other cars can’t and often gets louder applause. This is because we’re neutral, independent and unusually well-liked in a highly competitive industry – which makes us the perfect agitators.

If we can inspire one of the giants, such as a contract management platform or a global law firm’s AI assistant, to use our content as part of their training data, that would be transformative. It would be even more powerful if they replicated one of our prototype features. Either step would do more for climate-aligned contracting than anything we could build or maintain on our own.

Using AI to make climate risks visible in contracts

Our first experiment was a blunt but powerful proof of concept that explored the following hypothesis:

If users are given a tool that analyses the language of their contract, suggests relevant clauses, and ranks these based on business impact, they are more likely to use climate-aligned clauses than if they had to search manually. They will also feel more confident that they have identified the most relevant and effective clause for their context.

The tool demonstrated two key capabilities:

- Surfacing climate risks. By linking existing contract language to relevant clauses, the prototype extrapolated the risks those clauses were intended to address, giving users a clearer view of potential exposures.

- Recommending improvements. It generated contract-specific guidance to help strengthen terms, close gaps, and align with emerging climate and regulatory standards.

Technical approach

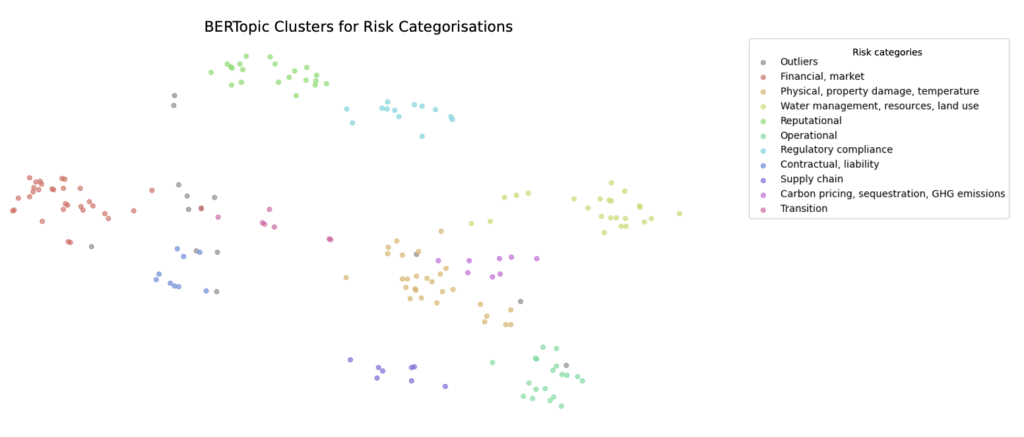

The technology behind this concept was a BERT-based, specialised Climate Litigation embedder paired with an LLM.

Simply put, this takes text and represents it as numbers. Every word becomes a point in a vast mathematical space, so instead of treating words as isolated, we embed them within a context. In our case, that context is both climate and law. We created a domain-specific embedder – a model trained so that each word is represented not just generically but in a way that reflects both its legal and climate-related meaning.

Using this specialised embedder, we analysed contracts using the following process:

- Sentence-by-sentence analysis. Each contract is broken down and transformed into its numerical representation in the climate-legal space.

- Finding climate-aligned language. Each sentence is identified as either climate-aligned or not climate-aligned, a designation made by a model pre-trained for the task. These results are highlighted for the user, and the document is given a designation between ‘None’ and ‘Strong’ as to how much climate-aligned content it contains.

- Mapping against known clauses. We also compare those embedded sentences against our library of clauses, which are already mapped into the same space. This step allows users who receive a less than ‘Strong’ categorisation to consider other clauses for implementation.

- Classifying risk. A custom risk taxonomy links each clause to specific categories of climate risk. Recommended clauses are shown with the risks they mitigate, allowing users to see which risks may remain unaddressed in their contracts.

- Finding connections. The closer two points are in this space, the more similar their meaning. That allows us to detect when a contract echoes, omits or diverges from the climate-aligned clauses we want to promote.

By using this approach, the tool doesn’t just read contracts word for word but understands them in relation to climate-aligned language.

Risk dumping and designing for the wrong behaviour

As we developed this prototype and shared it with colleagues, something became clear. The tool’s patchy accuracy could be fixed with refinement, but the real problem wasn’t technical at all. It was behavioural: how climate risk is understood and then acted upon in practice is still emerging.

At the same time as we were developing the prototype, another team was carrying out research into the professional obligations of lawyers and how they advise on climate risk within existing advisory frameworks. What they learned was that the framing of “climate risk” brings both opportunities and problems. On the one hand, it can help lawyers identify exposures early and build resilience into deals. On the other hand, if handled badly, it can lead to unintended consequences. For example, the potential for clients to reallocate climate liabilities down the supply chain, shifting costs and responsibilities onto the smallest suppliers, least able to bear them.

Take a hypothetical apparel company based in the UK.

The UK company uploads its supplier contracts into our tool, which highlights missing climate provisions. They then dutifully insert a raft of stringent obligations, but without providing support or shared accountability. The results? Small, low-carbon textile suppliers in Bangladesh or Vietnam absorb all the new risk, without the resources to manage it. What began as a climate-aligned improvement for the UK apparel company becomes, in practice, a new form of inequity.

That is just one risk among many, and there are also real opportunities to design for better outcomes. But to get it right, we need to understand how lawyers are currently framing climate risk, what clients are asking for, and how early adopters are navigating these challenges in practice.

So we paused work on the climate risk emphasis in the tool because our goal is to demonstrate good practice in how contracts can help reduce carbon emissions quickly, but also fairly.

It’s always tempting to plough ahead, polish the demo and call it progress. But one of the quiet superpowers of being a non-profit is that we can pivot early without sunk-cost pride getting in our way. Our prototypes aren’t meant to be products. They’re useful enough to spark conversation and, importantly, disposable enough to discard when they start heading in the wrong direction.

Designing for positive action, not risk shifting

Working with the feedback from lawyers on our team, we rethought the end goal that we wanted to motivate users towards. Instead of simply surfacing risks, what if the AI highlighted opportunities?

The new prototype takes a contract and not only spots gaps, but also shows exactly which of our clauses could strengthen it and how each one contributes to reducing emissions. The emphasis shifts: from defensive posturing (”how do I avoid being sued?”) to proactive alignment (”how do we design this agreement to reduce emissions?”).

Analysing a sample contract with little climate-aligned language

Analysing a sample contract with good climate-aligned language

View on GitHub the code for the model, and the code for the static prototype.

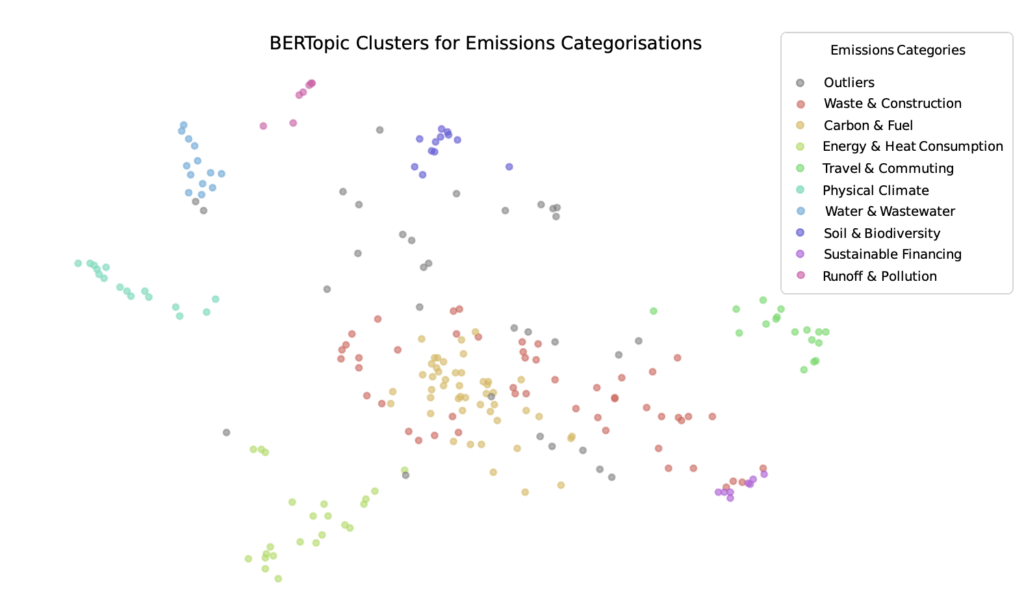

Embedding clauses by emissions categories

Luckily, there was a fairly easy technical shift to be made. We still begin by analysing each sentence, finding climate-aligned language, and mapping against known clauses. However, at that point, rather than connecting the clauses to potential risks they could mitigate, we instead connect the clauses to the most closely related emissions sources.

This reframes the output. Users still see how much climate alignment exists in their contract, but now that alignment is tied to opportunities for emissions reduction rather than to potential pitfalls. The cadence of the interaction becomes proactive rather than reactive.

What we learned from users

We took the prototype and tested it with 10 participants who represented both Global North and Global South perspectives, including practitioners from large international firms and regional consultancies.

- Strong validation: Users see clear value — the tool speeds up first-pass contract review by ~80–90% and helps bridge the “where do I start?” gap for less experienced users.

- Intuitive design: The visual gauge and yellow highlights were consistently praised as simple, quick, and effective for spotting issues and aiding team reviews .

- Trust and credibility: Users trust TCLP content and see the tool as credible, but want stronger reassurances on data privacy/security before using it with live contracts.

- Areas for improvement: Clearer links between flagged contract text and recommended clauses; ability to download/export marked-up contracts; regional/jurisdictional settings; and suggested replacement text rather than just risk flags .

- Future opportunities: Industry-specific clause packs, emissions categorisation (Scope 1, 2, 3), integration into CLM/review platforms, client-facing versions, and use in training modules for legal teams.

“This has the potential to significantly speed up contract review and drafting,” said a sustainability law specialist.

“This can be improved by providing clearer connections between uploaded contracts and recommended clauses, thus providing context for the tool’s analysis against clause libraries,” said an academic researcher and contract strategist.

“It would be great to have a feature to download the marked-up contract as a DOCX file with highlights or comments, enabling junior lawyers to easily share analyses with senior colleagues,” said an in-house legal designer.

Reflections and what’s next

The research surfaced some clear points of friction, but it also reminded us why we started.

If we can inspire one of the giants, such as a contract management platform or a global law firm’s AI assistant, to use our content as part of their training data or to replicate one of our prototype features, that would be a major step forward. It would do more for climate-aligned contracting than anything we could build or maintain ourselves.

If such a feature lived inside a mainstream platform, barriers like privacy, security, and workflow integration would already be solved by the context in which it operates. That’s the leverage point we’re aiming for.

So the question isn’t whether we keep polishing this single prototype. It’s whether we keep exploring new ideas and do what a non-profit does best: staying light, experimental, and provocative. Our value isn’t in competing with commercial products, it’s in sparking ideas others can scale.