News & Insights

Our next steps in scaling the impact of climate aligned contracting

Gradually, then suddenly, we’re seeing AI take over the knowledge economy, from software development to the machinery of government, there is a fundamental transition taking place. Our work is no different, and we’ve experimented over the last 18 months to understand better how we can be part of this change and make sure that we aren’t left behind. Now, we think we have an approach to ensure that we will deliver impact on a scale we couldn’t have imagined even 12 months ago.

We will enable our content to be machine readable and distributed throughout the artificial intelligence (AI) and legal tech systems that are currently transforming how knowledge across law is managed. And alongside that, develop and promote a range of prototypes for how our content might be used across legal tech. Combined, this will give us the ability to embed climate-aligned contract language into the next generation of legal (and general purpose) large language models (LLMs), and create our own set of tools to help legal professionals integrate our work into their legal products.

Our partnerships with the Patrick J McGovern Foundation, a philanthropic organization dedicated to advancing artificial intelligence and data science solutions, and Unboxed, the brains behind the gov.uk petitions site and more, will expand the scope and reach of this work.

We are looking for a group of lawyers and professionals who work with them to come with us on this journey and help us understand the ways we can improve your professional tools and reach more individuals and organisations with climate aligned contracting language.

I’m Felix Cohen – the new Digital Lead at the Chancery Lane Project. I am, as LLMs so often love to say, “Not A Lawyer“, but as a lifelong technologist, I’m fascinated by the parallels between the formal language of coding and legal language and how both fields will be changed by the advent of LLMs.

“All software construction involves essential tasks, the fashioning of the complex conceptual structures that compose the abstract software entity, and accidental tasks, the representation of these abstract entities in programming languages and the mapping of these onto machine languages within space and speed constraints.”

Seeing AI tools coming to change the way we work feels scary. Law is a naturally conservative practice, and like software development, may become unrecognisable with the impact of LLMs. We can take solace in what Fred Brooks says above, by building tools that remove the accidental complexity of legal work and allow us to focus on the essential complexity, become better software engineers and lawyers.

The LLMs are here

I sit on the board of my building’s ‘Right To Manage’ company, a legal construct introduced to allow leaseholders to act in some of the capacities of building freeholders. Recently we’ve been holding an interminable consultation on some interior redecoration work. As is the case with so many things in 2025 it has taken longer than we would like, and the quotes we have received have been higher than we had anticipated even a couple of years ago, and so many of the leaseholders have quite rightly been kicking up a stink.

What’s been notable is how many of the responses we’ve received have been ‘AI slop‘. In this case, AI slop meaning ersatz legal language written by an LLM, eagerly prompted by an exasperated leaseholder, and leaving us as directors quite concerned at vague legal threats and dramatic emoji laden lists of our many failures. These people come from a wide range of industries, and none of them are legal professionals, but the LLMs they’re using see this as a legal problem, and have produced legal-ese documents for them which are often fundamentally flawed but sound impressive. (don’t worry about me, once we got these folks onto a call we reached the same amicable resolution we’d have done if they’d sent us one or two line emails laying out their reasonable concerns).

General purpose LLMs like Claude, ChatGPT or Gemini can make for terrible lawyers; they are prone to hallucinate precedent, are tuned for obsequiously agreeing with their users, and are trained on vast data sets that mean their understanding of process, jurisdiction and technicalities are blurred at best.

I relate this anecdote to emphasise the world is changing around us. As William Gibson famously said, “the future is already here – it’s just not very evenly distributed.” What’s happened to the software development industry will happen to swathes of the legal industry, and we want to do our part to make sure that happens in a way that benefits lawyers, people who work with and for lawyers, and to our agenda, the natural world and environment.

Our partnership with the Patrick J Mcgovern Foundation will allow us to experiment and understand what that means.

We’ve shared the results of our initial experiments before, drawing on data science and user centred design . Embedded in this prototype is the ability to identify existing climate clauses in contracts, as well as highlight opportunities to include our clauses. This is a fundamental tool that supports lawyers who are managing climate risk for their clients when structuring their transactions and legal advice. Building on this ability to automatically detect and recommend climate-aligned contract clauses, and continuing to focus on our primary objective of aligning law with climate action, and the natural non-competitiveness that lends us, we are moving in three directions:

Building the technical underpinnings of climate focussed contracting AI

We know that creating socially and environmentally positive legal products relies on a deep understanding of both the law and its application, and industry specific practice awareness. Our climate-aligned legal content is so widely used because of the hard work put into it by our international community of legal, business and technical experts. We need to ensure that the same rigour is embedded in our legal AI tools. Happily, the solution to legally-sound AI is high-quality, trustworthy content, which we have in spades.

We’ve seen this in the creation of and use of our California Climate Disclosure Laws pilot. By building an original guide via internal legal knowledge and AI tooling, then iterating on the output with a wider community of legal professionals, we created a ‘human in the loop’ process. Despite deep domain knowledge, we are modest in size. However we can augment human knowledge with machine tools, scaling impact well beyond our expectations. In this case, we’ve been able to rapidly and dynamically update the original guide based on new guidance from the California Air Resources Board, a process which would previously have relied upon lawyers carving out valuable time on a moment’s notice.

We’re making these models of developing content and outreach a core part of how we operate, and we’re in the process of rolling out internal tools to help our legal team and wider legal community structure our content to be usable for legal AI systems.

Initially this means focussing on two technical outcomes:

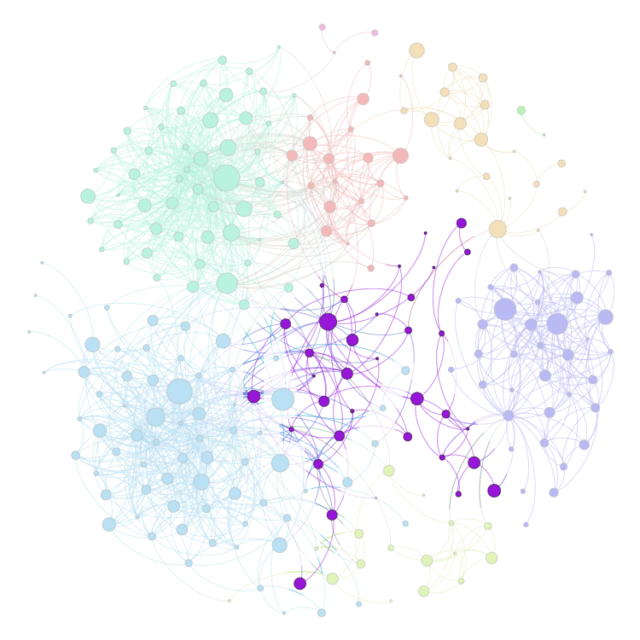

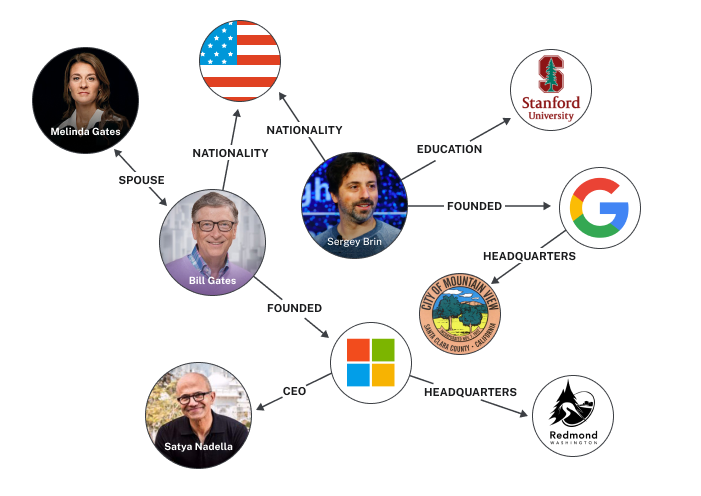

Our Knowledge Graph

In this context, a graph isn’t your traditional bar or line chart but instead a way to represent a network of entities and the relationships between them.

Our work here is making sure that we understand our legal knowledge both from the top down – what describes and distinguishes each of our legal documents from each other, and the bottom up, what terms and concepts exist across our legal content and connect it together. Once we’ve begun to understand this we can store the relationships and expose them to our own tools and the wider legal tech ecosystem.

Our API

API stands for Application Programming Interface, an astoundingly multipurpose acronym that could cover anything from controlling what songs play on a Spotify enabled stereo to querying stock prices from the NYSE – what unifies all these purposes is they are ways to describe how computer programs can interact with each other without human intervention. In the case of our legal documents and products, an API will mean a way for both legal and general purpose LLMs to access machine readable versions of our work, and to be able to navigate the structure of our categories and tags to autonomously explore the content.

Both of these tools will allow us to use our knowledge as a fundamental part of our infrastructure for building new legal tools – both on top of our graph directly and as part of the wider new economy of knowledge tools.

Identifying the problems legal language models can help solve, and prototyping those solutions

Internally, we’re spending time thinking about how we build prototypes and tools on top of this technical foundation – as my predecessor Alaric King concluded, our advantage is we can “do what a non-profit does best: stay light, experimental, and provocative”. The corollary to this is that we have to work with a non-profit budget for time and materials.

Testing our hypotheses about what tools will help to scale our impact can be done by adopting the principles of the lean organisation – create small prototypes, test them with real world users, and ruthlessly focus on what that research tells us is useful for lawyers operating in a commercial environment.

But once we start building we risk operating in the foothills of what’s possible – and missing the mountains – so we’re also keen to ask early on, what tools could be transformative for climate impact in the business of law.

Sharing this knowledge with law firms, legal tech companies and our peers to scale our impact

Once we’ve built the technical underpinnings of our ‘stack’, and created some prototypes for what is possible on those tools, we’ll be sharing our work here on our website and through the communities of practice we’ve created in our work so far, and you’ll see us at industry events, hosting our own conversations and discussing this everywhere we can.

All of this work relies on us operating within the legal community. The legal products we’ve created have helped us to reduce the carbon impact of billions of pounds worth of contracts, and the next decade holds so much opportunity to reduce and reverse carbon emissions, impact on the natural world and wider supply chain ESG.